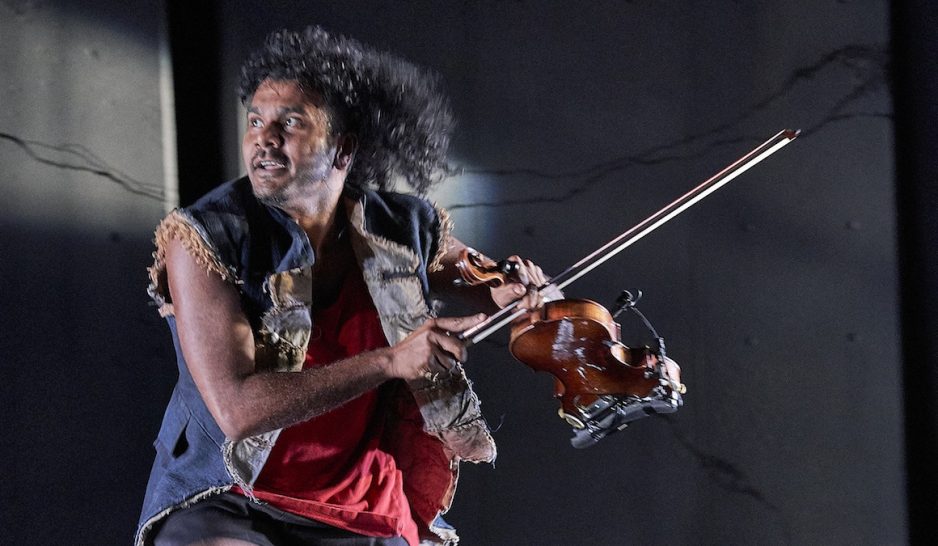

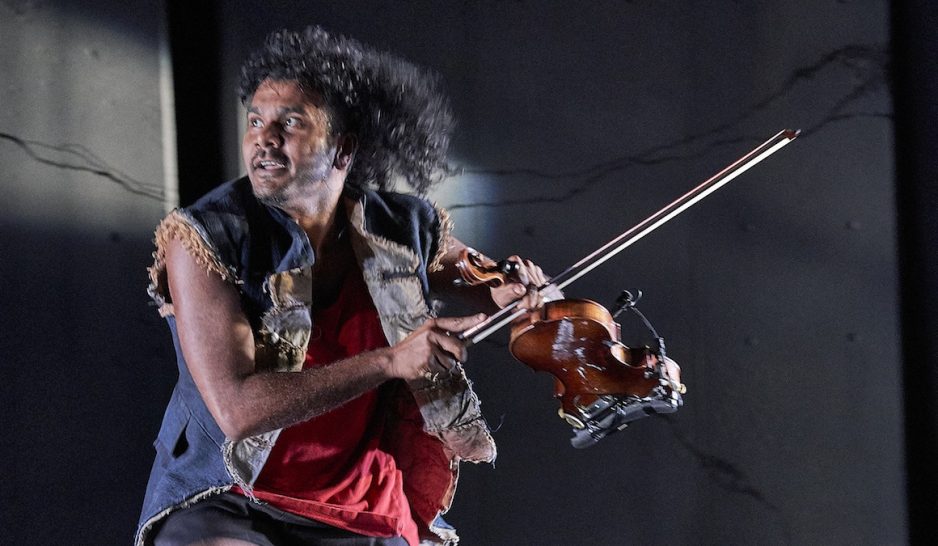

Eric Avery, Dancing with Strangers, Photograph: John Green

Home | Blog | One Reconciliation Week, Two Performances

One Reconciliation Week, Two Performances

I clicked on the official Reconciliation Week website to obtain a proper understanding of the implications regarding this annual period. The website speaks of working toward a future of better race relations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the wider Australian community. More importantly, in the opening paragraph, the website foregrounds this goal primarily through truth telling.

If I concentrate on this strategy, I would say that Marrugeku’s latest offering BURRBGAJA YALIRRA- Dancing Forwards which played to consecutive full houses each night at Carriageworks, fits the bill perfectly.

BURRBGAJA YALIRRA consisted of three solos, each providing a different facet in relation to this country, each performer sharing their personal truth.

First on the bill was Edwin Lee Mulligan’s NGARLIMBAH which translates as ‘you are as much a part of me as I am of you’. This was an interdisciplinary work of dance, film featuring Mulligan’s own animations and spoken word text. NGARLIMBAH tells of a dreaming history, a narrative of two dogs, one calm, the other wild and volatile. Throughout his performance the artist’s strong connection to place was paramount. I was made aware of the gravity associated with the responsibilities of being a custodian of one’s homelands. When Mulligan spoke of the demise of the volatile dog, of the red stain that was once the shed blood of the dog, my mind searched for the analogy, the message on which I was meant to meditate. I could only think about the impending construction of the Adani mine in central Queensland. In years to come how will those after-effects be chronicled in dreaming lore?

The succinct delivery could easily have been mistaken for a simple tale told in earnest. The dance felt like a contemporary rendering of a more traditional style. Mulligan’s body was often bent low performing a fluid repetition of gesture whereby one arm circled the head like a dog preparing for combat by cleaning its face for a better view of its opponent. The film featured a powerful series of animations, the dog with fire for eyes, the pink waterlillies with yellow stamens and the country yielding its birthmark of red ochre.

Miranda Wheen was second on Marrugeku’s bill. If truth telling were the most important element in art making then Wheen’s work MIRANDA could easily measure its success by this. MIRANDA acted as a veritable mirror reflecting back to the audience the overwhelming nationalistic ethos driving the country, and the world at the moment. Wheen began by dancing a fragile and genteel version of the early settlers through the narrative of the quintessential Australian classic Picnic at Hanging Rock. She was at once vulnerable, often portrayed as a diminutive figure in a large unforgiving landscape by falling to her knees to an equally genteel sitting position. As the dance progressed she stumbled repeatedly. Wheen’s floorwork was fractured, consisting of a comprehensive sequence of jagged isolations, alternating with standing sequences, beginning as a series of light steps and skips which slowly morphed into an enchainement of more rigid balletic language, before Wheen eschewed her white lace skirt for a pair of shorts to transform into a character resembling the very essence of an imperialist entitled nightmare.

Here Wheen’s skill in the portrayal of a character, which was the sum of all things abhorrent, was consummate. I found myself in awe of her ability yet slightly disappointed that she chose to give stage time to this facet of our community. I would’ve preferred to witness a performance that featured experiences closer to that of Miranda’s own. For Miranda has been working with minority cultures for quite a while, going to Kolkata with choreographer Annalouise Paul and taking workshops with celebrated African danseuse Germaine Agogny in Senegal before taking up her role as dancer collaborator with Marrugeku. Wheen’s relationship with these minority artists is much more complex and harder to define I am sure, but also maybe much more constructive, rather than the frightening creature she so easily inhabited, to an audience which was already converted and perhaps seeking alternative paths for themselves.

Special commendation must be made to Stephen Curtis’ set design as the industrial features of the Carriageworks’ interior were replicated and scored with an outline of rugged mountain ranges. This spare set consisting of three large panels also served as projection surface, successfully emphasized the complexity of Australia’s First Nations relations, ideas and ideals against a contemporary global temporal space.

Lastly, Eric Avery performed DANCING WITH STRANGERS combining his music and Aboriginal language skills with surprisingly subversive humor.

Avery opened his performance with a melody composed on the violin with the assistance of a looper pedal and proceeded to dance to it. Avery then told the story of the first fleet from a written record of one of his ancestors. It was at first a whimsical tale of canoes attached to looming white clouds, of strange dances in tight formation including alien hand gestures. By reducing the regimental march with its resolute salute into a curious dance Avery turned our very ominous history on its head to deliver a surrealist fable.

Avery’s piece was both slightly shambolic yet profoundly insightful. On this occasion Avery had a slight technical malfunction yet Avery managed to capitalise on this by turning his remaining mic into another character. In the work Avery proposed an alternative future whereby the languages of this land aren’t dying but reviving and thriving (and still plausible I might add). The seemingly improvisational delivery afforded me the space to engage and re engage with the work in situ, rather than as afterthought in the foyer or in my home. Words were utilised as elements of abstraction in lieu of didactic renderings, coupled with dance which saw Avery regularly alternate from colonialist to Native. The ingenious use of a reversible coat, coupled with his violin, became a weapon, a shield and a source of shelter.

The ending to Avery’s piece was equally powerful as he spoke his ancestral tongue into the fading light. I couldn’t help think that maybe it won’t be cockroaches that endure but the language as it calls from the landscape, as friction on the wind.

The other performance I experienced over this official Reconciliation period was SSHIFFT by Thomas E. S.Kelly and Dancers as part of Karul at Pact theatre in Erskineville.

This work was also a slightly surrealist offering performed by Kelly with his partner Taree Sansbury and her sister Caleena. The budget was tight but the work punched well above its weight creating a full atmosphere from its sci-fi imaginings.

The premise was founded on a the trappings of a support group. This was not your average support group though as the affliction on trial was the ability to shape shift.

Shape shifting plays a large part in Australian First Nations creationist histories. Many of the dreaming histories feature this process of metamorphism, from the Southern Cross formed when the first man and his two wives flew to the skies as Cockatoos, to the formation of the rivers by the black duck Kubitha who was guided in her dreams by small people called Tuckonies (NSW lore).

The work opens in an unnamed community hall where tea and ‘bickies’ are on offer as a form of sustenance for the ensuing ordeals. Three characters Virginia (Caleena), Colton (Kelly) and Denise (Taree) each regale us with their afflictions. Virgina is new to shape shifting and describes the physical transformation before demonstrating her ability. Denise is called upon but reluctant to share so Colton, a seasoned attendee, comes up to share his story which is actually a dreaming history, the almost universal story of the Seven Sisters, the Pleiades constellation.

It is the rendering of this history which sees Kelly’s dance vocabulary really take flight. In this, Colton’s section, we are treated to the most explicit example of Kelly’s mix of small gestural vocabulary melded with the sharp rhythmic shifts which punctuate a whip like series of undulations of the torso. These shifts are made more dramatic by the clever use of roaming lights, manipulated by the other dancers to create a kind of shadow play reminiscent of early black and white Alfred Hitchcock movies.

This is followed by a duet by the sisters hailing a departure from Kelly’s usual choreographic repertoire which rarely utilises partnering. In it the sisters use their breath to synchronise movement, audible above the sound of the music. They also utilise counterbalances to convey a strong sense of interdependence to great effect.

There are other group pieces to round the work out, but it is the solo performed by Taree, which acts as scene stealer from the moment she takes to the taped square on the floor to begin. Taree’s physicality is mesmerising and addictive as she hunches low, her torso resembling that of a predatory quadruped.

I hope this won’t be the last we see of SSHIFFT as it marks the beginning of a more sophisticated type of theatre craft from Kelly with plenty of scope to further explore the potential intricacies of each character and forge links to the larger implications this work could tackle.

Vicki van Hout