Home | Blog | NAIDOC 2024

NAIDOC 2024

Happy NAIDOC week you fla!

I have done my countrymen proud by jump starting my NAIDOC week celebrations with my attendance at NAISDA Dance College’s annual mid-year concert titled Legacy. The title was taken from a poem I wrote to commemorate the official relocation to the Central Coast at Kariong Parklands over a decade ago. As usual the NAISDA mid-year show featured works by both teaching staff along with a selection of short choreographic offerings from the student cohort. In hindsight I think I was lured to a ‘staff meeting’ so I would see the show before the official opening that night.

I was honoured to see and hear my words on the stage, given a new life. The poem chartered the reasoning behind the inception of the college, while operating as a homage to Carol Johnson its founder.*

My second activity in the lead up to NAIDOC week was the attendance of Marrugeku’s Cut the Sky, a remount over ten years in the making. Yes, you saw that right, Cut the Sky’s illustrious extended world tour was, like everything else, cut off at the knees by that pesky COVID virus.

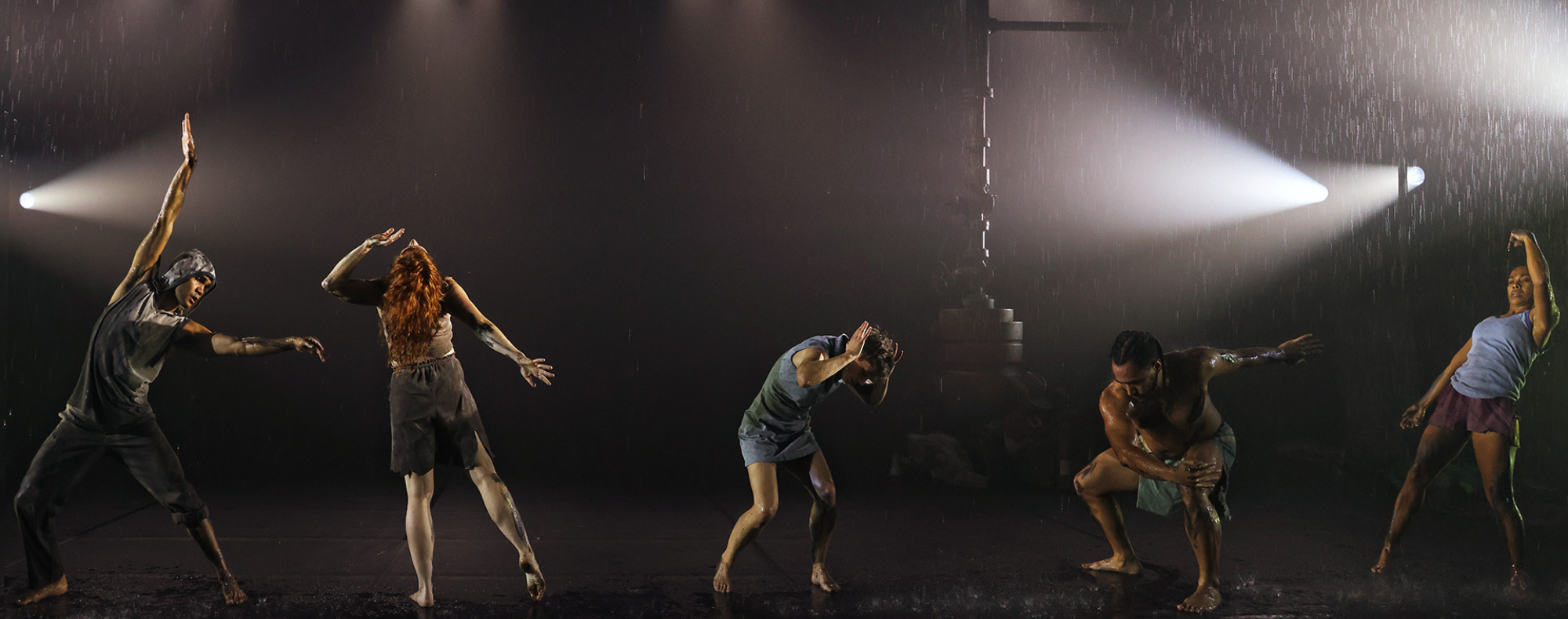

Cut the Sky is a dystopian dance theatre piece aiming to foretell a dismal fate of the planet approximately fifty years hence, however it seemed to represent the environmental crisis of the present with alarming accuracy. Cut the Sky literally acts like a weathervane featuring portrayals of extreme weather events which are mirrored in the depictions of the extreme human behaviours (namely greed) which precipitated the condition of our current climate, and as ramifications of our anthropogenic acts.

Initially created in 2012 as a response to the impending gas mining of the Jabir Jabirr country sixty miles from Rubibi (Broome) in the Western Australian Kimberely region, Cut the Sky seeks to give voice to the resultant ruptured interiorities of the land and its inhabitants.

What makes this work interesting is not the overall aesthetic, which is evocative of George Miller’s Mad Max film franchise, nor the dance, which is superbly executed by a fantastic ensemble ranging from hip hop dancer Samuel Hauturu Beazley, to actor and traditional dancer Emmanuel James Brown who lives in Fitzroy Crossing and led by the inimitable Dalisa Pigram, but the drive to present works that defy Western dramaturgical convention. I was first caught off guard by the dramaturgy of Marrugeku’s previous work Le Dernier Appel / The Last Cry. Le Dernier Appel / The Last Cry defied the format of a presentation in three acts whereby a theme is established, a problem is introduced and a resolution is offered. Instead Le Dernier Appel / The Last Cry threw us in the midst of political chaos, beginning as a rumble and ending with the lights going out in mid-flight of a social maelstrom. Similarly Cut the Sky defies convention by placing us in the middle of the environmental mess and although the end came with the relief of rain after an unbearable drought, the downpour also left us the audience in a state of uncertainty as its force equalled the dry in its intensity. Additionally, Cut the Sky animated the land through the voice of singer Ngaire Pigram firmly placing the work within the Australian First Nations canon whereby everything in existence is related equally, interwoven as part of the fabric of the Dreaming. In Cut the Sky Man is certainly not at the apex of existence but at the apex of the grandest folly currently in play.

Highlights from this work, and from many of Marrugeku’s works featured the consummate marriage of characterisation and physicality of Miranda Ween. She played a range of characters, from crazed soothsayer able to intuit the disturbance from the natural world, to the corporate culprit which white washes the deeds that sanction ugly acts with mercurial aplomb.

Shout out to Emma Harrison whose backbend in the opening defied gravity and which set an expectation of excellence, of pure liquidity of movement, which was a delight to uphold. And lastly a shout out to Taj Pigram, a newcomer to the Marrugeku fold, who in this work made his mark in a lightness of being, depicted in a sequence featuring so many barrel turns I’m getting dizzy just recalling their relentless number. A young dancer to watch out for.

From Marrugeku I hotfooted it to Parramatta Riverside Theatre to catch two of a triple bill with the overarching titled sixbythree presented by FORM Dance Projects.

I did intend to catch some audience members on the way out of the first piece titled Lien by Lewis Major but was doolallying at home and missed the whole shebang. Not that I was going to actually partake of the first work because it featured a series of one-on-one experiences that I didn’t wish to deprive someone else of. Hence all I gleaned in passing from an audience member was that it was refreshing to sit on stage for once. Upon hearing this I was intrigued and have decided never to be selfless again.

The second on the FORM Dance bill Cowboy, was a solo effortlessly danced by Michael Smith and facilitated through a collaboration with Queensland’s Gold Coast company, The Farm. I just love that they describe themselves as the “gateway drug to contemporary dance”. Watching Cowboy I wholeheartedly concur. For Cowboy was indeed a show of inclusivity, geared for a wide demographic, with just the right amount of audience participation to make you feel a part of the action without feeling as if you’re under the spotlight.

Cowboy feels like it belongs in a NAIDOC themed blog because, while Smith is not Indigenous, nor his imagined setting, which placed us in a sprawling frontier landscape somewhere in the United States the work was an homage to the depiction of those men whose lifelong destiny was to nomadically roam the open plains of their country. Like Blackfellas on walkabout.

Due to its broad appeal Cowboy could so easily have been a shallow event, but it was not. It was funny and poignant and the perfect vehicle for Smith to explore expressions of queerness. Like the movie Brokeback Mountain, Cowboy used the genre that depicts traditional ideas of masculinity to challenge them. Unlike Brokeback Mountain the show was not angst ridden, nor painfully ernest. Instead Cowboy was a celebration of the ambiguity, the complexity of what it is to be male. Refreshing even.

I just loved when he lassoed himself, becoming both the cowpoke captor and calf, or when he and his imaginary piano playing damsell pranced off into the heart shaped sunset, in matching rope reins attached to their thighs, in the aftermath of an equally spirited drunken bar brawl. All I can say is thank god the Riverside foyer was covered in fake grass because his coverage of the otherwise concrete quadrangle featured many iterations of the classic death drop.

I don’t want to give too much away because Cowboy has a ways to go before it rides off into its final sunset. If you get the chance to, catch it.

In comparison to the antics featured in Cowboy, the last item on the FORM Dance bill titled Quartette was a neo classic offering. Quartette began with a short work by acclaimed British choreographer Russell Maliphant followed by three pieces by South Australian independent Lewis Major, who was mentored by Maliphant and who incidentally has just been appointed Executive Director of FORM.

Maliphant’s work Two x Three was as its title infers performed by a cast of three dancers. It was decidedly sculptural and repetitive in nature, the intricate sequences unfolding slowly providing a palette for us to meditate upon, like a moving mandala. It wasn’t until I saw the lighting design of a black square within a square, which gave the effect of dappling as the dancers moved to the outer perimeters of the illuminated frame, that I recognised that element as a singular creative signature. Michael Hull’s lighting design is so distinctive I experienced a sense of deja vu as my mind cast back to 2013 seeing Aakash Odedra performing Maliphant’s Cut as part of his quadruple bill of solos titled Rising also performed in the Lennox theatre of the Parramatta Riverside complex.

The ensuing three pieces by Lewis Major in Mort Cygne, Lament and Epilogue imbued the Quartette program with an overarching uniformity of neo classic virtuosity. Maliphant’s ability to evoke an abstract interiority was extended by Major. This ability to precipitate a state of mesmer, named after German physician Franz Anton Mesmer who “theorized the existence of a process of natural energy transference occurring between all animate and inanimate objects”** which we now call hypnotism was epitomized in Major’s final piece. Epilogue demonstrated this tactic of virtual teleportation through the deployment of continual circularity through the solo dancer Clementine Benson’s coverage of the stage coupled with her constant transitioning of levels in space. This was combined with a gestural vocabulary which displaced a fine film of fine white pigment which hung in the air to frame Benson in soft white clouds, enhancing an ethereal quality.

In parting I will again bring this work into the Indigenous thematic fold by referencing my work Briwyant which paid homage to the depiction of dots and lines of Aboriginal painting which is designed to transport you to the place of The Dreaming and of which I am sure I was taken when witnessing Quartette, and heralding a promising beginning to my ensuing 2024 NAIDOC adventures.

Until next month readers.

Vicki Van Hout signing out.

FORM Dance Projects

Blogger in Residence

*https://www.facebook.com/share/p/wgzR9gTH1ri78zrx/?sfnsn=mo&mibextid=6aamW6

** “Franz Mesmer – Wikipedia” https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Mesmer