Home | Blog | MAU & Djuki Mala

MAU & Djuki Mala

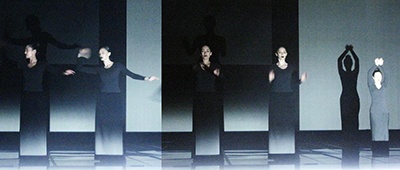

Image: MAU, Stones In Her Mouth

This past weekend was a whirlwind of dance, three shows in as many days. Throw in a workshop and two post-show Q&As and my head is full of post-performative contemplation.

MAU’s Stones In Her Mouth was haunting – dark, stark, measured, devoid of hue and full of dramatic importance, while remaining without narrative. In contrast Djuki Mala’s self-titled show was colourful, funny, earnest, poignant and filled with so much buoyant energy, I thought someone might literally jump out of their skin.

Lemi Ponifasio’s Stones in Her Mouth featured nine Maori (NZ) women on stage. Djuki Mala – six young Yolngu men (NT).

Both works employed projection. Lemi (presented in Bay 17 at/by Carriageworks) used the projection as a lighting source, creating large strips, dividing the stage and adding texture as a subtle shimmer/flicker, combined with LED lighting in the form of a small square placed like an angular moon, and down-stage as a horizontal line on the floor, both blinding and momentarily obscuring our vision to create and enhance the image of dancers floating in and out of view, like mirages or ancestral memories conjured from long past. I was seated right up front and the effect was powerful. Lemi revealed, in the lecture/workshop afterward, that his use of lighting to both obscure and highlight action is an effect deliberately employed to heighten focus.

Djuki Mala opened at the Seymour Centre as part of Reconciliation Week celebrations, with the director Josh Bond addressing the audience. He shared information from the group’s initial meeting in preparation for the tour. They found that each member had experienced the loss of a young relative to youth suicide in the past year. This was to be the impetus for the rest of the show, with the use of projection as documentary, peppering the night with tidbits of information through interviews with company members and the wife of the first manager on the prevalence of death, the birth of the group and the crucial role Djuki Mala plays in the community.

It was revealed that their famed dance, Zorba the Greek, which had gone viral after being posted on YouTube, was created as a gift of thanks by the brother of a young girl who was billeted in Darwin by a Greek family.

This was a beautiful sentiment, made even more powerful as it was put into context for me. I had watched a similar act attending Garma (a Yolngu festival in the Northern Territory) for the first time in 2007, where a dance about trading with the Macassans was used to show appreciation for the community’s participation, with a real exchange of money taking place in performance, to acknowledge their skill and send them safely back to their homelands. The act of dance was used to facilitate the continuity of cultural practice, not just as a means of decoration. This, along with the fusing of eclectic forms, including Yolngu traditional, bollywood, hip hop and Motown, born from relative isolation, away from the easy access of global technology, in favour of imported dvd’s from the local one-stop shop catering to almost every domestic need, is what makes Djuki Mala an exceptional dance company.

Using the conventions of the blackbox theatre, finding an epic or cosmological relevance within a contemporary format, as a means of breathing new or continuing life into existing cultural form specific to place/country, is becoming more common as a device to ensure cultural perpetuity, vibrancy and visibility. One such example, Marrugeku’s new project Cut The Sky, is using the ongoing mining controversy in the Kimberly region as a springboard to highlight the global desire to devastate more and more pristine habitats. Marrugeku uses Yawuru language, community consultancy and regular visits to country. Lemi also addressed this when asked about the juxtaposition of old (Maori song and chant) with new (electronically generated digital sound score) musical form. He spoke of culture being associated with the past, the exotic, the mythological, and that past and future don’t exist for him. What matters in the theatre is to be prepared and ‘to be present’.

Lemi’s uncompromising abstract declaration of Maori female strength makes no apologies, introducing the nine women through repetitive chant, movement and images becoming more declarative and increasingly energetic, from the steady pulse and deft precision of the poi (ball and string hand held instrument), to the power of the stick and its ability to cut a swathe, to the appearance of a lone body bathed in strips of blood red. He does not stand down, instead gaining in intensity. Some people walk out. Mostly adults with children (this time).

In the workshop/lecture Lemi states that when we go to the theatre we have to be prepared to leave. In fact the theatre is not about the innocuous dinner-date experience, it is a ritual with more considerations. Lemi shared his desire to make the audience’s body tense and alert by gesturing this with arms folded tightly across his chest as he described his objective.

Djuki Mala‘s audience was comprised of whole families, countrymen, seasoned theatre-goers mingled with relative newcomers. The audience was quiet as the men opened with Baru/crocodile, followed by Brolga and spirit dances, before launching into Zorba which was met with uproarious cheers and laughter that grew in momentum, as hybrid form gave way to modern urban.

Two distinctly different shows, with vastly different production values, both sharing a similar strong impact. Both performances significant in themselves and in the way cultural expression is utilized and perceived through the contemporary idiom.

– by Vicki Van Hout