Home | Blog | GRAD SHOWS NAISDA + Sydney Dance Company PPY

GRAD SHOWS NAISDA + Sydney Dance Company PPY

Hi guys, it’s that time of the year when all things wind down and then inevitably cranky into gear after the end of year celebrations are done and dusted. If you haven’t heard from me for a while it’s because my former gangsta street cat appropriately named Growler got into some unknown feline fracas and subsequently we have been to the vet more than I care to think about. Talk about needing some kind of regulation. So, I have been sleepless sans Seattle because being a feline he can bypass several cone devices and contort himself to lick his open wound like a bucket of buffalo wings. It’s a vicious cycle where I seem to come off second best.

Yet again I digress.

I have seen and participated in a lot of dance activities this past month and a half with two end of year collegiate performances in NAISDA Dance College and Sydney Dance Company’s Pre Professional Year programs, which were topped off by SDC’s last ever “New Breed” program, giving emerging artists a platform to make a significant choreographic splash on the concert stage.

Oh, and did I mention I was the 2025 recipient of the Lucy Guerin Indigenous Choreographic Residency, held at both Carriageworks and in the Lucy Guerin XYZ studios in North Melbourne. I haven’t forgotten that I promised some video evidence proving how very fruitful that endeavour was. But alas my puddy dilemma thwarted my immediate action on this directive. So, watch some heretofore undisclosed space for some unabashed unpacking of my very own creative endeavours.

Now back to the end of year productions.

NAISDA Dance College was up first. We were actually tag-teeming in Carriageworks’ bay 17, me with the Lucy Guerin residency, and then the NAISDA student body utilising the space as their dressing room.

As opposed to last year, most of the works were choreographed by the developing artists framed by the choreographic shaping of artistic director Charles Koroneho. Koroneho is an independent conceptual artist based in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, whose work often creates a visceral impact and his decision to act as a performative presence, topping and tailing the show, lent an air of ceremonial gravitas.

The invitation to remount Koroneho’s work He Taura Whakapapa (A Rope of Genealogy) was inspired. The feigned simplicity of twining rope whilst reciting one’s lineage speaks so eloquently to a temporality that spans multiple centuries. The repetitive ducking and weaving acted as an equivalent to the type of meditation that the sound of the yidarki creates, and the act of placing dots on a canvas to make a painting shimmer, in order to transport us to the dreaming.

It was heartening to see a collaborative piece choreographed and performed by the three soon to be graduating students Alira Morgan, Lena Parkes and Drew Walker. Appropriately titled Real it reflected the individual strengths of each performer; Alira and her feisty gymnastic physicality, Lena and her lithe long-limbed body moving with ease and an air of grace, and Drew who possesses the rare ability to surprise you with her staunch unapologetic energy. The use of the stage in this work was expansive, with each dancer initiating a section only to have the other dancers join in, creating a flocking effect that doubled as a metaphor for a collegiate relationship developed over the course of their studies.

Other notable mentions within this program included the compositionally tight work titled The First Cry from Jorja Burgess which felt like it could well have been choreographed by a Bangarra Dance Theatre alumni in that both the pacing and the gestural vocabulary resonated with Bangarra’s distinctive aesthetic. Tessarna Cora piqued my curiosity causing me to ponder what beings may have existed underneath the rolling fabric framing her entrance in All That We Are. Blake Escott’s Save Our Files represented an impassioned indictment on the diversity and complexity of the colonialist effect on Aboriginal people. This was reflected very clearly in both the costuming and the extensive partnering sequences. While the video component in Neville Williams Boney’s Thigabilla Gunni (Echidna Mother) made the most impressive use of the scrim. As the dancers moved behind it they become a part of the last projected image to evoke the same kind of eerie quality of artist Tracy Moffatt in her desert series and which is epitomised in her film Night Cries.

This year I don’t know if it was the sheer numbers, but the Yolngu dancing was THE BEST I have seen in years! Whenever I see this Saltwater/ Freshwater song cycle performed I want to jump out of my seat and join in the magic of it. However, I had to make do by replicating the punctuating cadences in my chair, alongside NAISDA producer Jasmine Gulash, who was doing the same.

From NAISDA to SDC’s PPY. The 2025 Revealed program felt decidedly longer this year in comparison to the year in which my choreographic input was included. Perhaps this is because the extended training program in this lineup was reflected by the inclusion of a choreography titled Throng by Richard Cilli, which was performed by the PP1 student body. Featuring second on the bill and so tightly crafted compositionally, with deftly performed vocabulary, that I was unable to discern the difference in experience between the first and second year casts. However, it was the combination of the handheld props, comprised of two large woven disks, together with the musical accompaniment driving the piece, which consisted of a composition titled Sidewalk Dances (Fourteen Moondog Pieces) by Johanna MacGregor, which set it in a unique world of its own.

Wanting to know more about the motivation for Cilli’s work, I was inadvertently led down a rabbit warren, whereby I discovered Moondog was a real person whose name was Louis Thomas Hardin. Hardin was an American trail blazing musician, composer and erstwhile poet who was blinded at the age of sixteen by the mishandling of a dynamite cap, moved to New York where he was mistaken for an eccentric homeless man for choosing to dress in a hat of horns as a Viking so he wouldn’t be mistaken for Jesus. More importantly Moondog is remembered for influencing musical artists across many styles and genres, with his rhythmic complexity and cross-cultural influences including North American First Nations ceremonial music, including Steve Reich, Phillip Glass, Frank Zappa and Charlie Parker. (I have made a mental note to ask Cilli whether this factored into his choice of music and or underpinning physical and or conceptual impetus.)

The evening actually opened with Zee Zunnur’s The Other Angels. In the program notes Zunnar aptly described her movement practice using the imagery of shape shifting invertebrates charged with the task to hunt and haunt. This methodology Zunnar brands as ‘Morphology’ produced an unfolding series of striking moving images, each endowed with equal dramatic weight. As the work progressed I found myself thinking of the pioneering modernists who created their seminal dance dramas replete with a series of similar kinetic sculptural sequences. Perhaps one of the most quintessential for me, as a self-confessed ‘Graham Cracker’, would be Martha Graham’s Primitive Mysteries created in 1931 on an all-female cast. A standout moment from so many was the solo whereby a dancer slithered transversely across the floor repetitiously contorting her body, creating a mesmeric effect in the foreground, as chaotic energy brewed forth from the ensemble behind her.

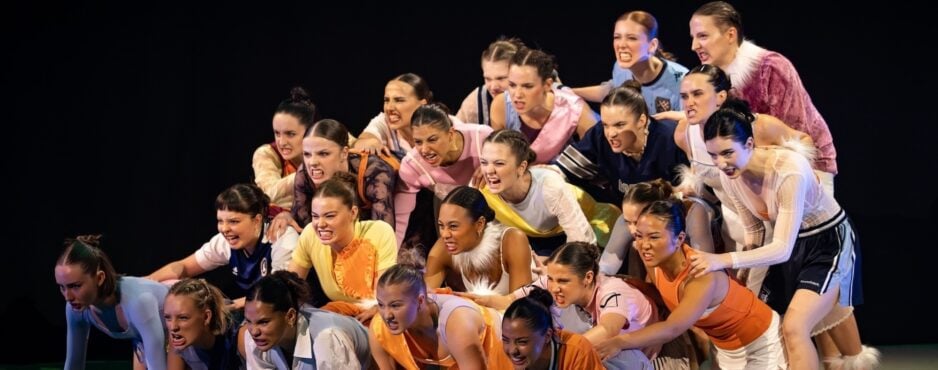

Local Sydney choreographer of growing renown Emma Harrison was third on the PPY bill, offering a playful indictment on power dynamics in her dance theatre work Top Dog. This piece provided the perfect antidote to an evening of serious contemporary dance. Not that the themes depicted in Top Dog weren’t seriously relevant. Harrison did a brilliant job addressing themes associated with gender equality, bullying and compulsory conformity expressed through the overarching machinations of competitive dog sports. Whereas the other works on the bill transported us to mysterious other-worlds, Harrison transported us to a hyper surrealist current alternate in the immediate. The playful attitude and sass with which the piece was devised and presented gave the audience the opportunity to see and hear a facet of the PPY performers normally associated with the spontaneous moments of joy and discovery that happen while you’re in the process of making serious contemporary dance. As a performer I relish this liminal space, that when executed at its best, has you guessing whether the performers are actually performing at all, or just letting a hidden part of themselves loose.

With so much going on one could easily underestimate the utilisation of choreographic craft that is required to realise this type of work, from the spatial placement facilitating the unfolding of each vignette, so they are allocated their own discrete denotation and dynamic texture, while seamlessly interweaving more readily recognised dance sequences without compromising either expressive components.

Thomas E. S. Kelly’s opened the second half of the evening. I feel I have to admit up front I have a particular bias when it comes to Kelly as we are Wiradjuri kin and over the course of nearly two decades I have been his teacher, his mentor, his dramaturg, a co-director and most recently a performer for him as part of his company ensemble in Karul Projects. I know that Kelly’s dance is a powerful vehicle for driving Australian Indigenous cultural perpetuity. I recognise the dance language he employs, its relationship to his ancestry and to the ancestry of other Indigenous countrymen, from the sharp and decisive movement of the head and feet, to the gestures that speak of a relationship with the universe that is nonhierarchical–familial. I understand his reasoning for using the entire cast at his disposal is to express community. I understood that Kelly’s work operates as entertainment and ceremony through the exploration of his subject matter in Gibumm, the sky beings who hold and disseminate Dreaming lore.

Hence in Kelly’s work I was able to acknowledge the dance moments that felt pedestrian. As a NAISDA alumni the hardest thing to do when participating in the ‘traditional’ dance events is to be quiet. For the dance to be about the collective conviction that you are the Dreaming when performing those actions related to lore. One must almost forget about what one looks like and to drive the magic.

Part of the Revealed formula is to conclude the PPY bill with a work by Rafael Bonachela. This year was no exception. However, I recognised in this iteration of Bonachela’s Lux Tenebris – two things. Firstly, this final piece revealed just how much working with the four chosen choreographers had influenced the interpretation of this last work and secondly, how fierce the predominantly female cast was with the exception of James Snashall (who was also fierce). I have to apologise for failing to single out each outstanding solo and duet moment as these moments were not specifically credited but I am sure most, if not all, of the demanding partnering sequences were originally performed by men and women of the original cast, yet here these women were literally holding their own. Also hats off to the soloist performing what was originally Richard Cilli’s solo. You smashed it. If and when I find out who are responsible for the singular moments I will amend this blog.

Lastly. I understand how glorious it is to have such a large cast at your disposal and cannot fault the choreographers for this. It just makes it that much harder to identify the individual in every standout moment. Every time I witness these end of year/ graduation performances my hope for the future of contemporary dance in Australia is renewed and this year was definitely no exception.

Damnit– I think this is going to have to be a two parter. Stay tuned for my take on the last ever New Breed season!

Vicki Van Hout

FORM Dance Projects

Blogger in Residence

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of FORM Dance Projects or its affiliates.