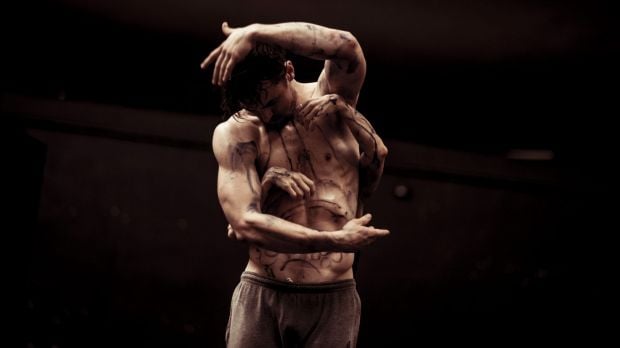

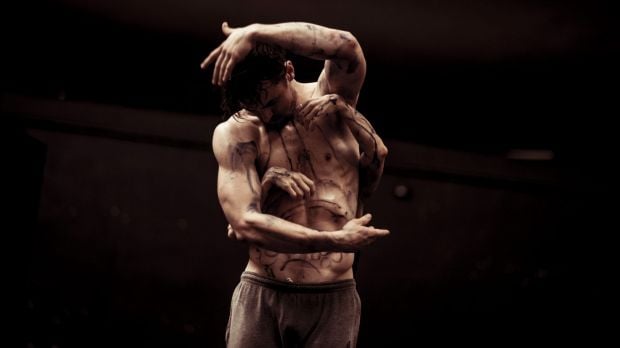

Cella Image: Pippa Samaya

Home | Blog | Is there ever a place for a star rating?

Is there ever a place for a star rating?

Woke up to a message on my phone this morning from a friend just wanting to quietly acknowledge our continued participation in dance. It put a spring in my step like a double shot of coffee never could.

I am prompted to also remember the day my most enduring dance mentor, and you know who you are, reminded me that it has been twenty years since I first walked into his studio as a dancer. When I initiated that particular dance foray I suppose I could’ve been considered close to the hill that many don’t recognise until they are over it. By ‘normal’ standards that is.

Similar thoughts filled my head as I sat and watched Narelle Benjamin’s Cella, performed with Paul White, as part of the 2018 Sydney Festival dance line-up at Carriageworks.

Let me begin with the obvious. These guys were breathtakingly phenomenal. The work unfolded seamlessly as two bodies rolling in anticlockwise polarity became one complex organism, limbs working as visceral extensions of one continually morphing entity. This biological realisation was set on a bare stage filled by pockets of light, which the performers traversed and inhabited. Created by lighting designer Karen Norris, Cella was accompanied by an equally sparse sound score predominately engineered by Huey Benjamin.

Benjamin’s work draws heavily on her facility which has been honed through years of dedication to yoga practice. In this particular work, I recognised her maturity as a maker willing to place every facet of her lived body on stage. From the manipulation of her stomach as White appears to plunge his hands deep inside her abdomen, conjuring an image of faith healers able to bypass the dermal barrier to the internal organs, to the stretching of the skin that encompasses Benjamin’s tiny form, made elastic through childbirth, to the very image of pregnancy as Benjamin’s folded body is hidden under an oversized t-shirt, allowing for a surreal image of White to endure the final stages of gestation.

This past week I have been working with dancer Elizabeth Lea, who, like Benjamin, is also a very experienced performer and maker. Like Benjamin, Lea is drawing on her body, using it as a narrative source for a work in progress, Red, to be shown at Gorman House in Canberra and at Riverside Theatres later this year, as part of FORM’s DANscienCE: Moving Well event in June.

The common denominator in these two works, from two very different makers, is a daring lack of subterfuge, a willingness to share their vulnerabilities, to harness them and rebrand them as performative strengths.

While both White and Benjamin have never been what anyone would describe as average, they are a part of a shifting landscape, representative of a change within the community which has grown to facilitate and accompany the voices of diverse lived experiences including those with disabilities, and from cultural or ethnic minorities as well as the established ‘veterans’. It was the excellence of the work coupled with this shift which prompted me to want to write about a correlating shift in responsibility of the reviewer.

I believe it is our responsibility to shine a light on inclusivity and diversity rather than judge worthiness. I believe we must be careful about how we frame artists. As reviewers, we are one of the first to influence how a work should be perceived.

Does it follow that there is a need for specialist reviewers? Out of the Sydney Festival there has also been growing concern that perhaps more specificity needs to be employed, certainly more sensitivity. A debate was precipitated by a review of Cella and of Dan Daw’s Beast appearing together in the same article. One was favourable and one was not. Both were given star value ratings.

(Actually, I read two reviews where the two shows appeared within the same article, which was probably due to convenience because they were presented in the same overarching venue. The other review didn’t come with a star rating.)

Sadly, I didn’t make it to Beast.

Firstly, is there ever a place for a star rating?

I have been employed to review several Australian Indigenous works which has been prompted because of an identified knowledge gap of Australian Indigenous theatre paradigms by the general audiences. Needless to say, I take my role seriously. I unpack historical precedence as well as cultural significance as Indigenous art making practices are demonstrations of cultural continuity, which act to strengthen notions of identity and relationships to country and kin. Of course, the non-indigenous audience wants to have a little of the knowledge but primarily they are there for an entertainment experience.

While I am buoyed by the fact that Narelle is in her 50’s, do I need to know everything about yoga and how ridiculously rare it is for her body to be able to execute her manoeuvres, to be able to experience her work satisfactorily? How much do I need to know about cerebral palsy to appreciate the choices made by Dan Daw in Beast?

I have come to the conclusion that it is my responsibility to help pique the audience’s curiosity. Maybe we need to censure our urge to criticise. As part of our job to inform the public in the lead up to an experience we need to be urging those audiences to live with these works longer than the initial residencies as bums on seats in favour of pit stops to wider exposure as portals of bodily research.

Vicki Van Hout