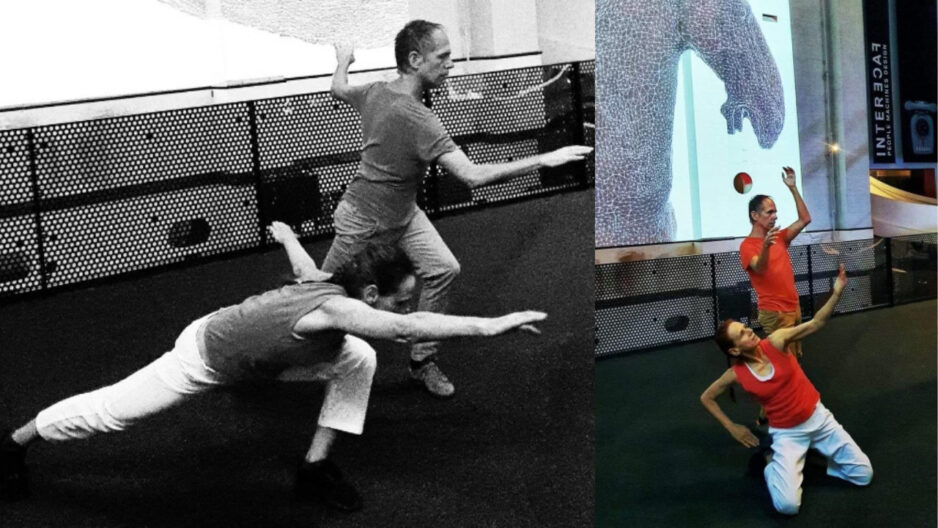

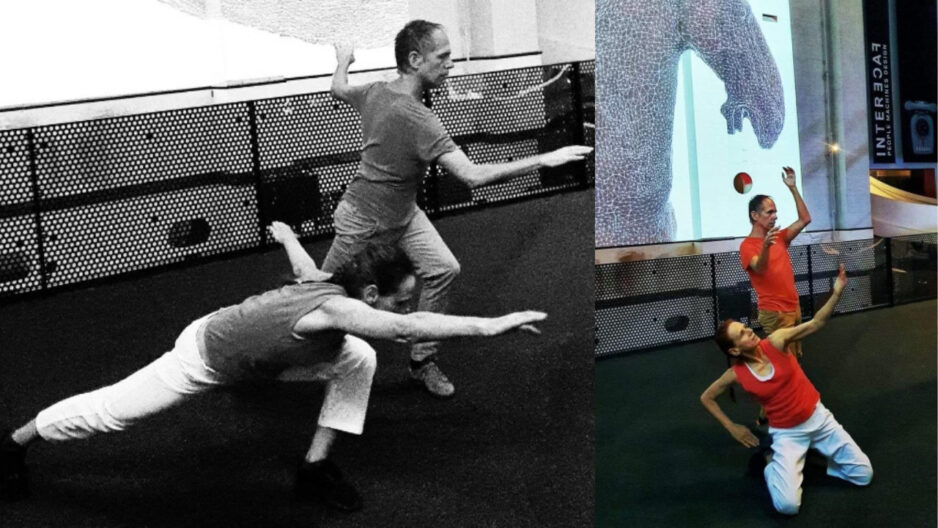

The Invisible Revealed, Vicki Van Hout and Martin del Amo - Image by Mark Andrew

Home | Blog | Dancing the agency of things

Dancing the agency of things

So, last month’s blog was dedicated to the dance I danced in acknowledgement of my relationship to a building, and this month, it seems, I have graduated from some unspoken test because I will be extrapolating upon that theme to engage you in coverage of those dances that lend agency to otherwise inanimate objects as subjects, and to subjects without conscious objectives.

As usual this blog begins with a short, somewhat self-indulgent recap of my experiences as a roving contemporary independent dance practitioner and for which I will not apologise. You’d be amazed Mr Morrison and Mr Albanese how much demand there is for dance to socially lubricate the community at present.

This time it is my personal dance adventure with Martin del Amo in the Powerhouse Museum, in the city as part of their regular Thursday evening soirees that I regale you with, in a tale of makeshift manoeuvres in sneakers upon hard wearing synthetic carpet with the potential power to administer short sharp shocks at short intervals. Yeah, did you know the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences or MAAS is the other moniker of the Powerhouse building (although nobody seems to have told them it hasn’t quite caught on), well they have a regular free to the public series simply titled Powerhouse Late from 5-9pm most Thursdays. In fact, this upcoming Thursday Jordan Gogos founder and designer of Iordanes Spyridon Gogos is curating an evening dedicated to fashion and wearable art (think of sporting a Jackson Pollock canvas on steroids), followed by a partnership event with Sydney Writers Festival, an evening dedicated to gaming, a Powerhouse Late event dedicated to West ball in homage to the NYC ballroom subculture, and lastly a retrospective dedicated to the LGBTQI community in mid-June. Suddenly, my Thursday evenings are all booked up in Ultimo.

Anyway, our evening performance was part of an exhibition titled The Invisible Revealed which features 26 exhibits which were scanned using nuclear technologies courtesy of the

Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) using their neutron beam and synchrotron X-ray facilities, combined with digital visualisation techniques, to ascertain their age and provenance.

Coincidentally, I have found that the process of ageing has had a strange effect upon me in that in my pursuit to thwart rigor mortis my dance has become loud and somewhat vulgar at times. Like a hot flush I can feel when I transition from a sophisticate into a lunatic as I give in to the surge of mania, and my limbs cleave the space producing overly energetic lines and sequences, whereby only fools and unwitting audience members remain in close proximity. Martin del Amo in comparison always seems to move as if he’s floating. Del Amo invokes a delicate air of curiosity, as if atmospheric currents are taking him on a journey belying his extensive experience in Body Weather training, which is geared towards honing sensitivity in relation to space and place. Despite our seeming incompatibility, I had the best time intuiting the porosity of the steel blades of samurai swords thousands of years old, refashioned and repurposed for a second life in WWII, to dancing the machinations of the artificial intelligence it took to uncover the age of a Persian rug and the composite construction of a frail wooden pony, amongst the many artefacts with del Amo. For our dance was as much about the discovery of aspects of each other as it was the objects; how to share the performative space and work in complement to each other as opposed to modes of combat, vying for the eyes and attention of the bystanding bodies.

Two weeks afterward I was alighting a train in Wollongong to watch another immersive gallery performative response by Ryuichi Fujimura, to artist Gary Carsley and architect Renjie Teoh’s collaborative installation in the round titled Illawarra Pavilion. The artwork itself was a surreal image depicting a combined contemporary urban Australian exterior drawing you into an Asian interior space. Inside and outside were simultaneously realised like an Escher optical illusion, and as viewers we were transported to the place of dreams, for it is only in the surreal realm that we can reconcile and inhabit those ambiguous spaces as if they were almost commonplace.

The artwork was composed of over 4,000 overlapping printed A4 pages glued to the four walls of the largest gallery space which was interjected with a collection of three dimensional artefacts accommodating several temporal, spatial, and cultural genres such is the Wollongong Mann-Tatlow Collection of Asian Art.

Ryuichi Fujimura is a specialist of Spartan gesture. Each time I watch his work I am both surprised and appreciative of his lack of clutter in physical expression. This is extremely difficult to achieve in our digital era when we are constantly bombarded with imagery, and assaulted with advertisements to buy this, or get that now, and pay for it later. Fujimura’s performance included a promenade followed by a simple physical gesture at various points or stations about the room whereby he would place himself in the image, whether that be lying on floor tiles depicted as a thin strip extending from the wall to create an impossible angle, or pulling back a three dimensional shutter to look at a view that was partially obscured by another shutter which was its static two dimensional partner.

Fujimura is also in possession of a unique yet equally understated sense of humour and in this performance I found myself chuckling in response to his actions. One outstanding moment featured his placement of a dinner plate with an image of an oversized eye up to his face so that it appeared as an upturned exclamation mark, or the painted image of Rene Magritte’s Son of Man (1946), except in lieu of a simple black suit Fujimura was dressed in black and white plaid, and instead of an apple hovering in front of his head, it was an iris painted on a cheap white plate from IKEA. Fujimura’s interpretation of the space gave us clues and cues for appreciation of the work and lent an appropriate light touch, which prompted me to position myself in various points in space in relation to it, which may not have been explored otherwise.

Lastly I saw Sara Black’s latest iteration of Double Beat performed at Riverside as part of the Dance Bites annual program. I say the latest iteration as I saw this work in development at Shopfront theatre as part of DirtyFeet’s Out of the Studio initiative in what seems like eons ago now, before the Covid epidemic hit, in 2018.

Because so much time has elapsed it seems like a whole new work. Or, maybe it is just the whole new cast of Sophia Ndaba, Isabel Estrella and Samantha Hines from the original Brianna Kell, Jasmin Lancaster and Cody Lavery that has made it seem so different from its earlier incarnation. Maybe, it’s because this incarnation was in-presentation as opposed to in-development. I did go back and view excerpts from the development at Shopfront and was surprised that I recognised all but one incarnation.

Whatever. It was beautiful. So nice to see three virtuosic female dancers performing with so much dexterity unaided or unencumbered by a male performer holding them up by a single finger as they pirouette for days, on ice picks for slippers. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. So refreshing to see slippery spines take precedence over gesturing limbs defying gravity. Not that there’s anything wrong with that either.

You can definitely see Narelle Benjamin’s hand in this work as mentor, as I saw glimpses of the same kind of vulnerability in the embraced duet between Sophie Ndaba and Samantha Hines that we witnessed in Benjamin and White’s coupling within their multiple award-winning Cella. Maybe it’s also something to do with the similarity in subject matter, for Black the heart and its many incarnations and manifestations for and over a lifetime, while for Benjamin it was in the interpretation of the basic structural, biological units of all living organisms.

Other simply exquisite moments were found in Ndaba’s body, which reacted like a Geiger counter to the changing proximity of the other two dancers and the closing image of all three chests rising and lowering in exhausted uniformity until they simply ceased to be and the lights came down.

Vicki Van Hout

FORM Blogger in Residence