Home | Blog | Classical Ballet: Success as a system of the regiment in the eternal search for beauty

Classical Ballet: Success as a system of the regiment in the eternal search for beauty

It’s Sunday and I am about to pedal on my pushbike, to Sydney Dance Company, to partake in a ballet class. I know all too well the arduous rigours the body endures in order to maintain this well cultivated façade. This is my weekend indulgence. I don the pink slippers and take my place at the barre and for an hour and a half I alternate between the joy of embodying the courtly myth and the frustration at my body as I try to weld it into delicate virtuosity. I am not particularly interested in world dance domination.

When I think of classical ballet I think of the femme fatale, of the ethereal fairy-tale, the elaborate sets and women floating across the stage on pointe shoes, soft undulating arms belying the furious footwork below. In the maintenance of that romantic image, the last thing I think about is colonial expansion. Yet this is what American dance scholar and choreographer Susan Leigh Foster describes in her paper Choreographing Empathy.*

Foster’s claims are threefold, using a combination of French philosopher Condillac’s theories on kinaesthesia and the physical transmission of empathy, in tandem with Feuillet’s notation of Baroque court dances (the pre-curser to classical ballet), to aid in the colonisation of the new world in the 18th century.

How does she do this? By drawing similarities between the fields of dance and philosophy and then drawing similarities between other disciplines of botany and science. Foster claims that colonisation was caused by classification.

How can the seemingly benign process of naming something lead to the European governance of the colonies?

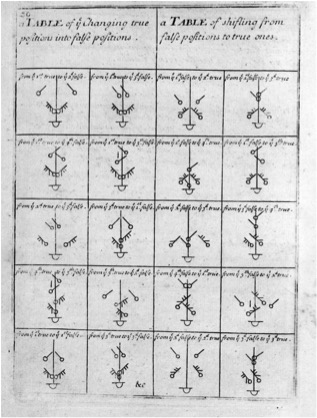

Beauchamp- Feuillet notation illustrating ‘true’ and ‘false’ positions of the body (left)

Beauchamp- Feuillet notation illustrating ‘true’ and ‘false’ positions of the body (left)

The object or concept/discipline to be categorised is components followed by a ‘universal’ process of reconstruction. It was in the presumption of a universal truth and subsequent acts of reconstruction that dominance and power prevailed. In botany, it was the method of categorising by appearance, as with the Beauchamp-Feuillet notation of dance in 1700, where dance was reduced to a physical act.

Stay with me.

Believe it or not classical ballet is not that old in relation to history of civilisation. About three hundred years. Before ballet there was (and still is) folk or ‘primitive’ dance, the dance of the people. Folk dances are about relationships, they are an extension of the spoken word, conducted with others. Folk dances are reflective of social practices belonging to specific communities and reflective of how people engage with each other with/in a specific geographic location.

After the introduction of dance notation, dance became a portable act of imagination. A dance could be created and learned in isolation. Dances became tangible commodities that could be bought and sold in the marketplace. The dances of imperial Europe could be transported to the colonies and anything that didn’t resemble the manufactured universal truth wasn’t recognised, or was amalgamated into the classical idiom.

Feuillet outlined the preferred dance environment as the flat rectangle with a front face, the basis of today’s proscenium arch theatre. Imagine if the parameters for the ideal dance arena were in the round from the beginning, how might our dances be created? How might technology have advanced to capture it? Would we have the video camera, which can only ever capture a two dimensional likeness, or would the hologram be a commonplace reality?

As a graduate of NAISDA (a college dedicated to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Dance), I remember the dances I was taught, by tutors from communities with an unbroken lineage of practice for thousands of years. They are an affirmation of the relationship to country and the distances travelled by ancestral beings, when they created all of the flora and fauna on it, by disappearing into and becoming a part of it. We literally make tracks, our feet interacting with the terrain, marking the same paths our creator beings traversed. Yet those steps, indicative of a wealth of knowledge affirmed in practice, were lost to many of the clans up and down the coastal areas of Australia. If indigenous dance were the mainstream norm imagine the theatrical space. Perhaps a mound like the one in Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Ochres would be a mandatory staging component in lieu of the raked stage. Maybe dance would live in and share football stadiums and cricket pitches?

Condillac uses two analogies to explain the connection of action and consciousness. In one he imagines a statue whose senses are all denied except breath and touch. From breath a sense of the internal is described, from the ability to touch oneself, a sense of the body and from an outward touch of the environment, a distinction between oneself and of oneself in the world. Again the complex reality of the individual quest is predominant. It’s not hard to imagine this as an extension of the coloniser’s ethos.

Through a seemingly benign scenario of two children, one gesturing to another for an apple, Condillac claimed empathy resided in the recognition of the gesture by the other. What is not considered is intent and the potential to wield power in this situation. Foster shares Condillac’s speculation whether the observer is feeling empathy or pity but notes he does not take into consideration the intent behind the gesture, whether it is engineered to elicit empathy or pity. This window for misinterpretation illustrates the shortfall in assuming that one person can ever really know or recognise the thoughts of another. Action and intent are not universal. Foster identifies the assumption to know another’s thoughts, and acting upon that assumption, as the basis of colonisation. Alternately, leaving a window of interpretation open, to speculation and imaginary participation, is a vital ingredient for theatre.

Amelia McQueen and Kristina Chan in Tanja Leidtke’s Twelfth Floor. Photography Chris Hertzfield (left)

Amelia McQueen and Kristina Chan in Tanja Leidtke’s Twelfth Floor. Photography Chris Hertzfield (left)

Armed with this newly acquired perspective on the process of colonisation through Susan Leigh Foster’s eyes, two dances spring to mind which may more accurately depict and utilise classical ballet vocabulary. Tanja Leidtke’s Twelfth Floor, set in a psychiatric wing of a hospital and we are made privy to the alternate logic that drives the actions of the ‘inmates’. The Matron, a nurse Ratchet type (from author Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, also set in a psychiatric facility), exerts her exacting power and authority through the quick clipped balletic phrases of her feet accompanied by short sharp gestures of the arms. English based Jewish choreographer Hofesh Shechter used balletic vocabulary, to literally depict the pervading presence of oppression, in his work Sun. Dressed loosely in costumes of the court, including the jester, Shechter illustrated hypocrisies around the behaviour of the gentlemen classes.

I am home now, recuperating from the mornings exertions, I have pointed my feet until they cramped and imagined possessing the long graceful neck of a ballerina, only to be confronted with the image of a sweaty footballer, with shoulders resembling a coat hanger, staring back at me from the floor length mirror in return.

Did I tell you I am enrolled in a Masters Degree at Macquarie University? It’s a whole new world where the ins and outs of dance are unpacked in minutiae. Hence this momentary side track. While I appreciate the insight afforded me through my burgeoning research, there’s nothing to beat the exhilaration of actually doing dance. I think I prefer my embodied reality, the one that escapes to palaces and nobility, no matter how politically ironic that may be.

*Susan leigh Foster 2005, Choreographing Empathy, Topoi, Vol.24(1), pp.81-91, Springer

– by Vicki Van Hout